I was advising some students the other day about harmonizing non-traditional scales and someone mentioned how it would be useful to have a list of harmonizations for every possible scale. I bragged that I could write a program in half-hour to accomplish it. Of course it took longer than that, but I quickly wrote a small python program to generate harmonizations for every possible scale and used LilyPond to typeset them.

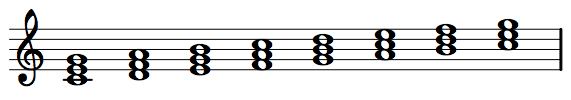

The harmonization for the major scale is pretty simple; you stack notes vertically following every other note in the scale:

In modern music it’s fairly common to use non-traditional scales to generate new and interesting harmonies. For instance, in the example bellow I have a 7-note scale that is very different from the good ol’ major scale. Right after the scale we have harmonizations for every 3, 4, and 5 notes of the scale. Also notice that we break the thing about having the interval in which we pick notes be the same of the horizontal notes (that is, having chords in thirds, fourths, and so on). This leads to very interesting harmonies.

By the way, this is one of the reasons I got into programming in the first place; to generate material to use in my compositions (using Pascal back in the 90’s, if you must know).

So, in order to harmonize every scale we need to know how many scales exist and the answer will vary depending to whom you ask. In a way a scale is an ordered set of notes, so I used the 129 pitch class sets with cardinality greater than 5. Here is a complete list of all pitch class sets. Some people will find that using prime forms is too condensed and doesn’t take in account a bunch of scales, but it’ll do for the purpose of this post.

The code to generate the harmonizations is actually very simple (with the help of my

in-progress python library). We harmonize the first note of a scale with

harmonize_first_note and use it in a list comprehension to harmonize every note of the

scale. The helper function rotate_set will generate every rotation of a list.

def harmonize_first_note(scale, interval, size):

i = (interval - 1)

indexes = [x % len(scale) for x in range(0, size * i, i)]

return [scale[index] for index in indexes]

def harmonize_scale(scale, interval, size=3):

scales = musiclib.rotate_set(sorted(scale))

return [harmonize_first_note(scale, interval, size) for scale in scales]

Here’s how we use it: A scale is defined as a list of integers (we are using integer

notation). Let’s put the major scale in a variable. The result of

harmonize_first_note will be, as expected, just the first chord (C major) as a list of

integers:

scale = [0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11]

harmonize_first_note(scale, 3, 3)

>>> [0, 4, 7]

And the result of harmonize_scale will be a list with the harmonization of every chord

in the scale. In the next example I’m using 4 as the chord size to generate tetrads:

harmonize_scale(scale, 3, 4)

>>> [[0, 4, 7, 11], [2, 5, 9, 0], [4, 7, 11, 2], [5, 9, 0, 4],

[7, 11, 2, 5], [9, 0, 4, 7], [11, 2, 5, 9]]

Finally, lets generate tetrads separated by fourths instead of thirds:

harmonize_scale(scale, 4, 4)

>>> [[0, 5, 11, 4], [2, 7, 0, 5], [4, 9, 2, 7], [5, 11, 4, 9],

[7, 0, 5, 11], [9, 2, 7, 0], [11, 4, 9, 2]]

The code to generate the LilyPond file is boring, so I won’t talk about it here.

Generating harmonizations for every scale is interesting and all, but it start to get

interesting when we can filter things. For instance, I may want to generate

harmonizations for the scales that have more than 4 notes and have consecutive intervals

greater than 1 semitone. This can be accomplished with filter_sets. This is how I’d

express the previous example:

filter_sets(lambda intervals, size: size > 4 and 1 not in intervals)

The function filter_sets accepts an anonymous function with a list of the consecutive

intervals in a set and the size of a set as parameters. If the condition in the body of

the anonymous function is met the set is returned:

def filter_sets(condition):

sets = {}

for forte, pc_set in musiclib.PC_SETS.items():

intervals = musiclib.intervals(pc_set)

size = len(pc_set)

if condition(intervals, size):

sets[forte] = pc_set

return sets

This is an example of how high-order functions can be used to abstract code. Also, the built-in function all is very handy to chain conditions. Let’s say I want to get scales that have more than 4 notes and have only 1 consecutive halftone and 1 consecutive whole tone:

filter_sets(lambda i, s: all([s > 4, i.count(1) == 1, i.count(2) == 1]))

Since I want to filter scales by interval content, it makes sense to write a small

function to help me. cond_interval_count abstracts the previous code:

def cond_interval_count(count_list):

return lambda i, s: all([i.count(interval) == count for

count, interval in count_list])

So if I want the scales that have no consecutive halftones and only 1 consecutive whole tone I can write it as:

cond = cond_interval_count(((0, 1), (1, 2)))

filter_sets(cond)

There are a few things that can be improved:

- Use some pitch spelling algorithm, like (Meredith, 2003) so we won’t have chords like C, D#, G

- Have better functions for filtering. The function I’m using looks for consecutive intervals but it would be better to search for every interval in the Pitch Class Set.

- Handle octaves better in the LilyPond generation. Some notes would be better on a different octave:

This post only scratches the surface of all things we can do. For anything more complicated than that I’d use music21, a nice and professional Python library for computer-aided musicology. But it’s interesting too see how far we can go with a few dozen lines of pure Python code and the use of nice abstractions. If you have an interest in this kind of thing, there are lots of Python packages for music programming and Notes from the Metalevel: An Introduction to Computer Composition is a nice book about the topic (but it uses Scheme, not Python for the code).